The many faces of tax-based costs

When you sell an asset, you must know its tax basis to determine taxable gain or loss.

This raises the question – what is basis? In its simplest sense, the tax basis is the cost of an asset, plus additional monies spent to improve it, less certain type of deductions (such as depreciation) against this adjusted cost.

If that wasn’t a mouthful to digest, basis can be far different from original cost. This means you might have a taxable gain when you sell something for less than you paid for it. Fortunately, the reverse is sometimes true. Under the right circumstances, your basis may greatly exceed what you paid, producing a tax loss.

The following are examples of the many faces of tax-cost basis.

Types of Basis

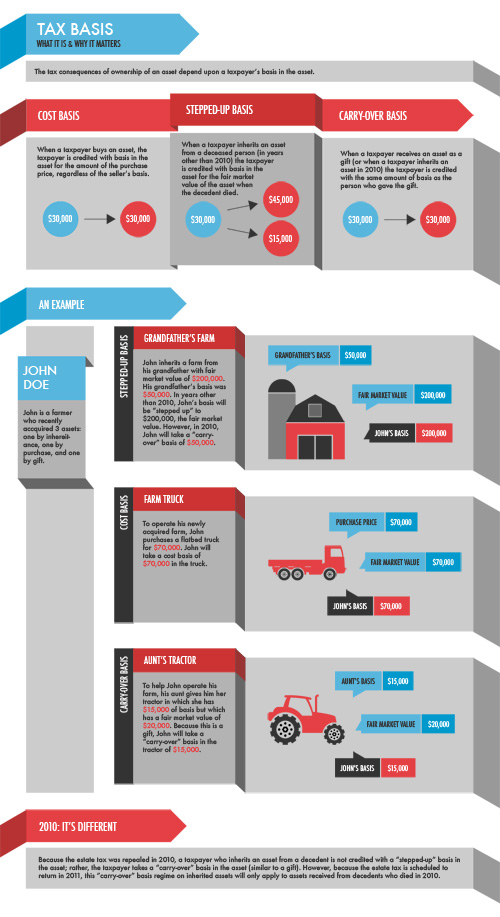

Cost Basis – This is the simplest and most common situation.If you obtain property in exchange for money, your initial basis is the amount of money you exchanged for the property.

Substituted Basis – If you receive property in exchange for other property in a transaction in which no gain or loss is recognized, your basis in the new property will likely be the same as your basis in the property that you gave up. Examples of this principle, which has broad applicability, are like-kind exchanges and property received in corporate reorganizations. A simple example would be if you had land that you paid $20,000 for that is now worth $100,000. You exchange that land for a different piece of land that is worth $100,000. Your basis in the new piece of land is $20,000. In exchange situations where money is used to even out values, it is called “boot”. Boot received generally requires gain recognition. Boot paid usually means that you have a divided basis and holding period for the asset that you acquired.

Carryover Basis – In some situations, a person (including an entity) who receives property needs to refer to the basis of the party that transferred the property. Examples of this situation are property acquired by gift or a partnership’s basis in property contributed to the partnership.

Inherited Property Basis – The basis of property acquired by inheritance is the fair market value at the date of death (or six months later if the alternate valuation was elected).

Adjusted Basis – Notice in discussing cost basis we said your “initial” basis is what you paid. Sometimes you recover your basis not when you sell the property but over the time that you use it. Depreciation deductions will reduce the basis in an asset. Also, your initial basis in flow-through entities such as partnerships and S corporations is adjusted for your share of the profits and losses and by distributions and contributions.

Negative Basis – This unique concept usually applies in the context of partnership accounting. When people loosely speak about having a negative basis in a partnership, it is because their share of the partnership’s liabilities is greater than their basis. In that case, abandoning the partnership interest would cause gain recognition. It’s not exactly negative basis, but it can sure feel like it; and it’s what a lot of folks call it. If you withdraw more than your basis in an S-Corporation, you trigger something called gains in excess of basis, which usually will be capital gain.

The point of the negative basis discussion is that basis sets a limit on the amount that you can deduct from flow-through entities. It is one of the several tests (profit-motive, basis, at-risk, material participation) you must pass through in order to to get a negative number into your total income.

AMT Basis – The alternative minimum tax is a parallel system for computing your tax liability. In broad generalities, it involves applying lower rates to a broader base. You get to pay based on which ever system comes out with the most tax. Your assets may have a different basis for AMT purposes than they do for regular tax purposes. As a general rule, if it is different, it will be higher

Here’s a chart that summarizes some of the differences: